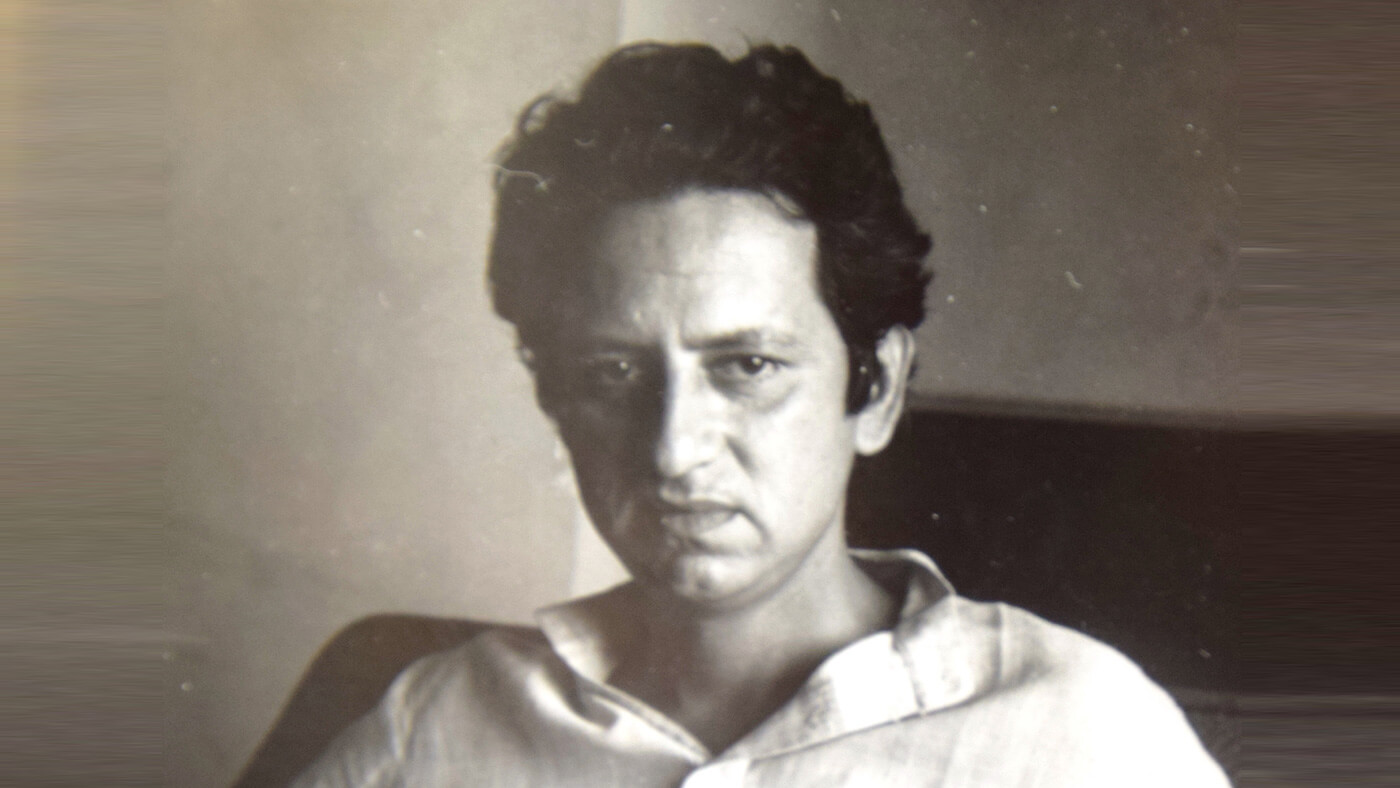

With the death of Kumar Shahani on 24 February at Kolkata, Hindi films and Indian cinephilies lost one of the best theoreticians, not just a filmmaker. Kumar along with his Film Institute Pune, colleague Mani Kaul had made the format of films in India upside down with their films, igniting a ferocious debate on the cinematic realism and also its formats.

Asked in an interview, “Do you think that there is any talent among the young filmmakers in this country, or is the Indian New Wave only so much noise?, the iconic Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak replied, “I pin my faith on Kumar Sahani and John Abraham. Mani Kaul is there too, but he has a tilt in his brain, slightly astigmatic, just like boys like you—always falling in love with words. Kumar Sahani is my best student. When he comes out with his films, it will be staggering”. This was of course before Kumar made his debut film Mayadarpan in 1972.

.

Along with his other illustrious batch mate of FTII, Mani Kaul, Kumar over the years emerged as the leader of the new wave, in Hindi films, which had a lasting impression on the filmmakers over the years. Though none of the films of Kumar and Mani got a theatre release, their films became the toast of the connoisseurs not only in India but internationally and the film society movement, which was at its peak in the 1970s.

Kumar was also man wedded to celluloid and was not comfortable with the digital medium. He believed that with Kodak shutting his celluloid film stocks production, the world was now susceptible to digital manipulation through technologies as far as reality is concerned.; a fact proven beyond doubt by the emergence if artificial intelligence. Celluloid, he thought was less susceptible to such manipulations, though from the first film onwards he has been experimenting with realities and his visuals in his films.

Through his 17 films, out of which only five were fictional, Kumar defined his vision of films for India which was in the process of defining Indianness in films, aided and abetted by a government under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi. Like most of his batch mates of FTII, be it Mani Kaul or Adoor, Kumar too made his first film through funding of the public sector Film Finance Corporation. Their films were a shock to the then commercial film sector, which Ritwik , their professor, used to describe as a “ gambling den”. Even in that new genre of film making, there appeared to be two schools, one led by Ritwik, who was the proponent of epic style and the other led by Ritwik contemporary Satyajit Ray who believed in realistic narratives. Though both despised the commercial genre and were deep into creative concerns, rather than commercial ones in filmmaking, they had their distinct style in approaching the viewers. While Ritwik followed the epic style with an emotional appeal to issues, formalism in Kumar and Mani’s films rejected emotional appeal while handling the most sentimental of stories like Uski Roti. John Abraham, another favorite of Ritwik, opening criticized Mani Kaul draining out sentimentalism in Uski Roti, much to the surprise of the ardent admirers of the filmmaker.

Total rejection of realist narrative in their films of Kumar and Mani had led to their cut off from a mass audience through regular film releases, which Adoor, John Abraham and many of their contemporaries managed. Some like Subash Ghai, their FTII colleague, went to a Bollywood success, through adopting some of the format of the commercial genre of films, but sticking to the new found narratives and visualization. Noting their complete rejection of reality Satyajit Ray had wondered whether their Professor Ghatak could have approved of such a trend in the emerging genre of Indian creative films. Ghatak’s own Meghe dhake Tara , was a roaring box office hit in Bengal and was a sentimental drama. Ghatak had scripted the Hindi box office buster Madhumati of the 1960s.

“Like a meal, a film, the vast majority of films, the kind of film that will be of concern to most of you, is made with the sole purpose of being consumed. As long as it stays in the cans, a film is dead matter. It comes to life and serves its purpose only in the theatre, in the presence of the public. The public then has to be taken into account –even by you with your diplomas and your dreams of a personal cinema, a radical cinema, a political cinema or what have you”, Ray told the 1974 convocation address of FTII, at a time when there was serious debate about the future of new wave films in India, especially following the rejection of “realist narrative” by Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul.

However, both Kumar and Mani remained an enigma in Indian films, dividing the most ardent connoisseurs into a fierce debate on their acceptability with audiences and viability as creative medium necessitating huge investments. “The two were inseparable in their rigor, their vision, but both took different paths, one went to Khayal, another to Dhrupad; one to Chekhov, another to Dostoevsky, one to Eisenstein and his Montage, another to non-Eisenstein and non-Montage, one to, Marxist Materialism, another to, if i may venture to say, Mystical Materialism, yet both moved towards Ghatak and Bresson, two radically different worldviews. For Mani, they both cured him of the sickness called realism – Kumar must have shared the similar sentiment but in a different phrase, perhaps”, a senior critic noted in his social media post.

In passing on of Kumar and Mani earlier Indian meaningful films have lost two stalwarts who questioned the existing narrative and visualization of even their own genre of films. Many consider both of them as the creative assault weapons of their Maestro Ghatak, who used indigenous narrative structures and cultural symbols to embellish his films, against the Western style of straight narrative propagated by Satyajit Ray. Kumar also emerged as the best Indian film theoretician in the process of defending his style of filmmaking. “Although known primarily as a filmmaker, Kumar Shahani has taught, spoken and written on a variety of subjects over this period, that include the cinema, but also politics, aesthetics, history and psychoanalysis. In these essays Shahani addresses diverse political issues, aesthetic practice, questions of artistic freedom and censorship”, said the introduction to his only book, a collection of years over a period of 40 years namely , The Shock of Desire and Other Essays published in 2017.

It is not just an end of an era in the passing of Kumar, but also spurts of new dawn nurtured by Kumar and his generation of filmmakers who dedicated a life time to create a new vision for Indian films, through their films and continuous engagements with the creative minds and connoisseurs of all genres.